- Home

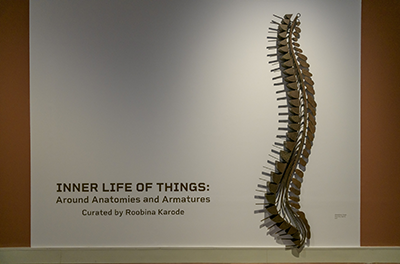

- INNER LIFE OF THINGS: AROUND ANATOMIES AND ARMATURES

Exhibitions

The Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) is delighted to present a new group exhibition titled, Inner Life of Things: Around Anatomies and Armatures curated by Roobina Karode (Chief Curator and Director, KNMA) at the Noida space of the museum. The exhibition brings forth independent projects by 15 artists whose investigations are rooted in the ecologies of co-existence as well as the enigmatic life of objects and materials beyond and autonomous from human perception.

INNER LIFE OF THINGS: AROUND ANATOMIES AND ARMATURES

26 April 2022 to 28 December 2022

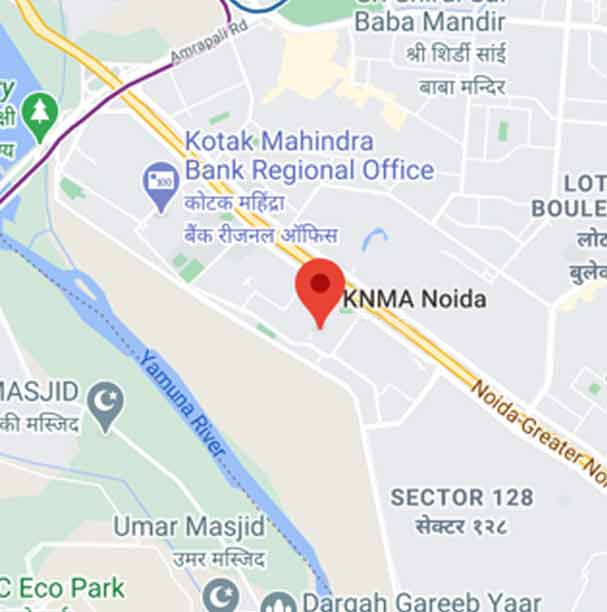

KNMA-NOIDA

The Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) is delighted to present a new group exhibition titled, Inner Life of Things: Around Anatomies and Armatures curated by Roobina Karode (Chief Curator and Director, KNMA) at the Noida space of the museum. The exhibition brings forth independent projects by 15 artists whose investigations are rooted in the ecologies of co-existence as well as the enigmatic life of objects and materials beyond and autonomous from human perception. The show opens at a time when, following the COVID-19 outbreak, attempts to claim what is humane and the social appear to be the most popular and urgent questions. However, unravelling a world pre-dating or even outliving the time of humankind on earth, the exhibition proposes a radical ethic of co-existence uncorrupt by the hubris of man. It speculates a place where the animate and the inanimate communicate with each other free from our mediation and control. The works of art in the exhibition, even when they appear to be testifying to the artist’s craft and imagination, give primacy to the very inner workings of the art objects: the anatomies and armatures that give the world its shape and character.

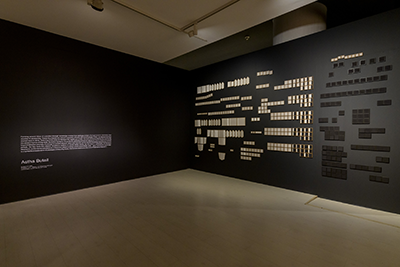

The four-panel watercolour painting of Lahore-based artist Ali Kazim (b. 1979) is executed in subdued shades and presented on a scale that overwhelms the viewer. It is inspired by the artist’s visit to the ancient Indus Valley Civilization excavation site near the river Ravi, and the ruins of culture it preserves. In her installation and video work, Vibha Galhotra (b. 1978) weaves a visual interpretation of changing landscapes through metallic ghungroos, and presents a calming ritual with her potted sapling by redeeming it of all the burdens of the city borne dust and grit. Anindita Bhattacharya‘s (b. 1985) acutely crafted lines of lushly detailed organic clusters and foliage in earthy hues, executed in the tradition of Mughal miniature painting, prompt the viewer to find the hidden and intricate patterns in nature. The idea of traversing lesser-travelled terrains and vast expanses is explored in Shalina S Vichitra’s (b.1973) landscape with a thousand white flags, inspired by Tibetan Buddhist dictums and the spiritual harmony that they seek with respect to the primordial laws and spirits of nature. Astha Butail’s (b. 1977) take on ancient methods of archiving and the tradition of carrying oral histories through Rg Vedic myths and metaphors marks a meticulous installation with minuscule prototypes of book-like objects.

Pulling the vantage point closer as if through a magnifying glass is Nibha Sikander’s (b. 1983) hyperreal images of critters and moths. They are manifestations of the artist’s entomological interest that seeks not to dissect, but to deconstruct the received notions of natural history. Reena Saini Kallat (b. 1973) presents the phantasmagorical within the natural world through her illustrations of morphologies and mutations of living organisms, suggesting an alternative evolutionary turn that is both surreal and humorous, bizarre and premonitory. Finding the threshold between nature and civilization in the ruins of agriculture, Shambhavi Singh (b. 1966) searches for the materiality of existence beyond the confines of function and utility.

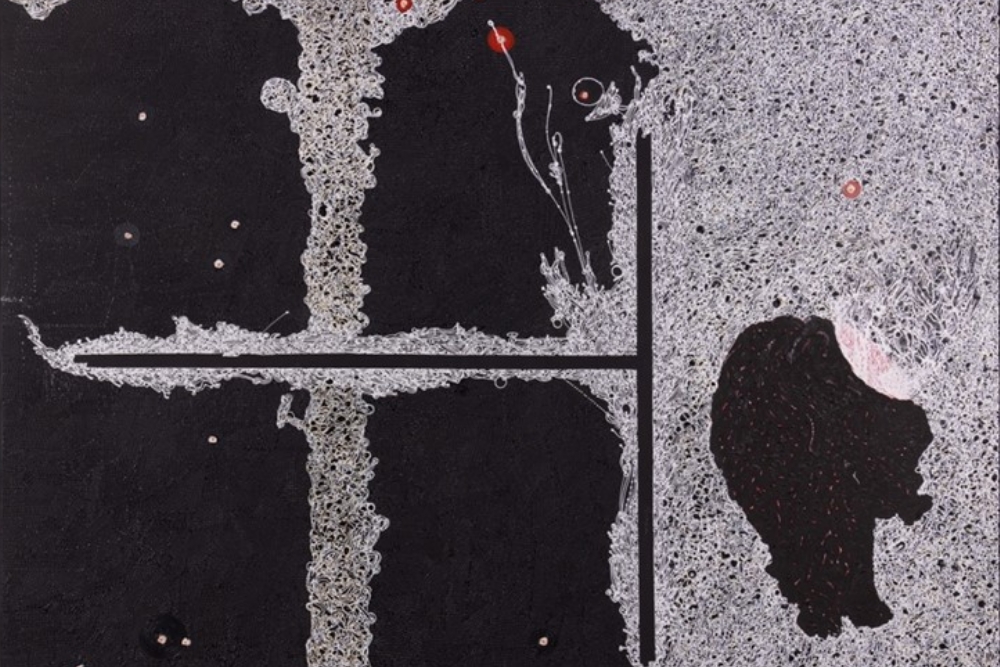

Debasish Mukherjee’s (b. 1973) work is an ode to the years from his childhood and the artisanal past. The work is poetic in its nature of folding, stacking and meticulously arranging the fabric of the white sarees from his late grandmother’s collection which now bears the insignia in the form of digital print portraits on both sides of the stack. Rajendar Tiku’s (b. 1953) small-scale works are the repository of a sense of belonging that is complicated by the melancholic ideas of homeland and the trauma of migration. In the context of the exhibition, these dwarfed chests of memorabilia appear to be the remnants of material memory and craft in the absence of their human custodians. Handling the tropes of migration and alienation is also the work by Rathin Barman (b. 1981) who investigates the intricacies of structural plans of houses that he moved from and into in order to locate the fragments of ownership and dissociation. They also give shape to the exhibition’s proposition on the inner life of things, an interior space that is made of the brute materiality of objects as well as the immaterial traces of spectral subjects. Dissecting the idea of architectural fragmentation further, Dilip Chobisa (b. 1978) rekindles the effect of assemblages neatly arranged in a grid. Often imitating structural drawings of engineers and architects, Kishor Shinde’s (b. 1958) compositions create illusions of high rises under construction, bridges dissolving in air, or mobile towers blurring away into a smoggy horizon. Exploring another dimension of grid-like overlay is seen in Rahul Kumar & Chetnaa’s (b. 1976 and 1981) collaborative work which finds resonances within urban surroundings and structures as the textured discs made in stoneware are arranged in a compact manner, contrasting with the blue and gold angular lines. Seher Shah and Randhir Singh’s (b. 1975 and 1976) cyanotype prints are careful studies of cityscapes and architectural motifs typical of the Brutalist style and the vestiges of an incomplete modernization that litter the contemporary.

_0.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)