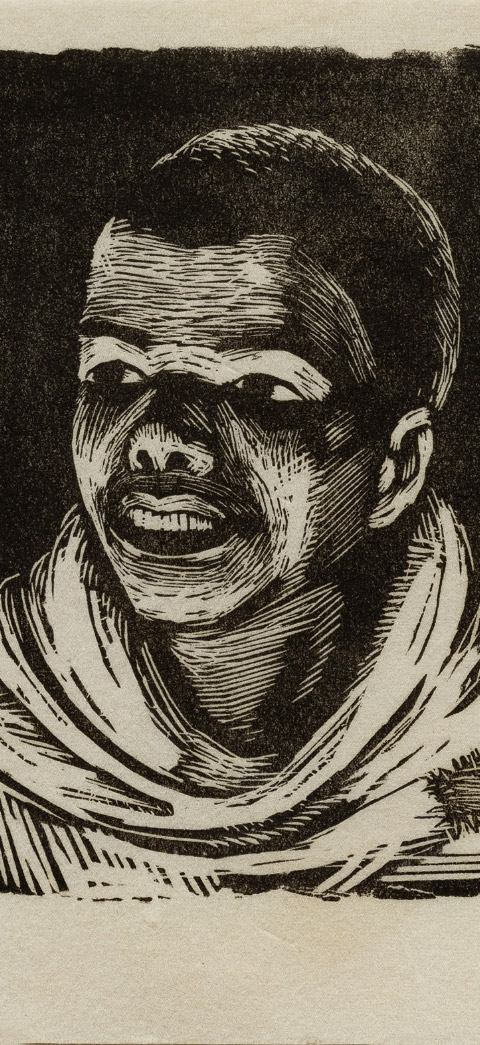

Experiencing a man-made famine which killed millions, the colonial violence that expropriated a whole subcontinent, a world war and numerous communal riots waged in the name of religion; it would have been the very meaning of humanity that shaped the worldview of Somnath Hore, one of the iconic artists of Indian modernism. He must have asked himself, if this could be a man—a hungry depleted body without flesh and evacuated into skeletal forms, with the pronounced rib cage and attenuated limbs, indistinguishable from a dying animal—then what does it mean ‘to remain human’? Reclusive and aloof from the glare of the mainstream artworld and witnessing the pain of the wounded and deprived, Somnath seemed to have posed this question again and again, to himself as well as to each of us.

His early works in the 1940s and 50s—driven by socialist ideas with his proximity to artists Zainul Abedin and Chittoprasad Bhattacharya as well as the Communist Party of India—were known for his heart-rending documentation of the Bengal Famine (1943), Tebhaga Peasants’ Movement (1946), and the condition of tea-garden workers in the north of Bengal, many of them published in the leftist magazines and circulated widely. In these swift yet veridical field notes, Somnath visually captured not only the horror of hunger and poverty, but the daily toil of the working class as well as the poignant moments of village meetings where women congregated as active participants and planned protests and strategies of resistance. Eventually by the mid-1950s after estranged from active political involvement and the school of socialist realism, Somnath moved to New Delhi and subsequently to Santiniketan, the places where he was sought after as a pedagogue and artist who specialised in printmaking, a medium that democratized art, and mentored generations of students.

Despite Somnath’s later distance from organised politics, his artistic horizon remained socialist and humanist. Similar to Käthe Kollwitz, the recurring question of poverty and survival, and the theme of care and compassion or the lack of the same in society, propelled Somnath to revisit the image of ‘mother and child’ time and again, sometimes through the gleam of bronze and at others through the strong fiery lines drawn or etched.

What started as a response to the Vietnam War and the socio-political unrest in Bengal in the late-1960s and 1970s, Somnath’s well known ‘Wounds’-series expressed the historical traumas of the time as tears, dents, impressions and gashes on paper-pulp surface. A similar approach was extended to his intimate bronze figurines as well, in which we see the clearest articulations of the impoverished figure of man that we find in the writings of Primo Levi: “Consider if this is a man/ Who works in the mud/ Who does not know peace/ Who fights for a scrap of bread/ Who dies because of a yes or a no.”

Paying tribute to an artist who stands tall in the history of Indian art for his empathetic modernism, the exhibition will present works from Somnath’s prolific six decades of artmaking. His art practice indeed is that rare and solitary white rose blooming in dark times, a nocturnal flower promising the arrival of dawn. To quote Eddie Jaku, another Holocaust survivor like Levi: “To grow a flower is a miracle […]. Remember that a flower is not just a flower, it is the start of a whole garden.”

- Roobina Karode